Why More Falsely Accused People Are Being Exonerated Than Ever Before

For the third year in a row, the number of exonerations in the United States has hit a record high. A total of 166 wrongly convicted people whose convictions date as far back as 1964 were declared innocent in 2016, according to a report from the National Registry of Exonerations released Tuesday. On average, there are now over three exonerations per week—more than double the rate in 2011. The number of exonerations has generally increased since 1989, the first year in the National Registry’s database. There are 2,000 individual exonerations listed in the registry as of March 6.

Experts say the increase in rate of exonerations can be explained, in part, by a growing trend of accountability in prosecutorial offices around the country. Twenty-nine counties, including Chicago’s Cook County, Dallas County, and Brooklyn’s Kings County have adopted second-look procedures and special review units that are tasked with looking into questionable convictions.

Historically, the convictions with the best chances of being overturned were those that got repeatedly reviewed on appeal or those chosen by legal institutions such as the Innocence Project and the Center on Wrongful Convictions. These cases tended to be high profile cases with defendants who received severe sentences.

The recently established conviction review units, on the other hand, designate resources to both violent and nonviolent crimes like drug offenses. These offices have been involved in 225 exonerations, seventy of which were last year. Thanks largely to these cases, nonviolent crimes accounted for more exonerations (44%) than murder and manslaughter exonerations (33%) in 2016.

The review units “reflect a growing recognition of the importance of the problem,” says Samuel Gross, a law professor at the University of Michigan, who is co-founder and senior editor of the National Registry. “Many prosecutors, police officers, and judges have learned that sending innocent people to prison is a constant risk—not a once-in-a-lifetime novelty.

Many point to changes in places like Harris County, Texas, home to the city of Houston, where the county’s conviction review unit has totaled 128 exonerations, or 15% of all exonerations in the U.S., since 2010, the first full year it was in operation. Harris County identified a problem that is likely systemic across the U.S. and has actively spent the last two years trying to right its wrongs.

It started in 2014, when a reporter from the Austin American-Statesman reached out to the district attorney’s office to ask about something he had noticed: a steady stream of years-old drug convictions were being overturned. In many of these cases, the so-called drugs were actually legal substances like over-the-counter medications that had been initially misidentified by faulty field test kits.

The field tests, which have been around since the 1970s and cost $2, are simple chemical cocktails that change color when illegal drugs like cocaine are added. But the color also changes when exposed to dozens of other compounds, yielding a false positive.

The district attorney’s office ascertained that there was a backlog of these drug cases in which the defendant had pleaded guilty. As ProPublica and The New York Times Magazine reported in great detail last year, the county worked to streamline the process of reexamining these cases, kicking off a mass reversal of convictions over the next two years. In addition, Harris County now no longer accepts guilty pleas in drug cases until the substance has been tested in a lab.

What’s remarkable about Harris County is that the crime labs there have tested suspected drugs even after a guilty plea. According to Gross, this is not done in many other major counties. And in many jurisdictions, evidence is destroyed once a defendant pleads guilty.

“If other labs did what they do in Houston, we’d see thousands of similar cases across the country,” he says.

Data from the National Registry show that more than half of exonerations involve perjury or false accusations. This problem is particularly prevalent in homicide cases and child sex abuse cases. Mistaken witness identification is often an issue in sexual assault cases.

A second report released Tuesday authored by Gross points to the apparent racial disparity in wrongful convictions. Gross’s analysis found that almost half of the exonerations in the national database are black defendants, compared with 39% who are white.

Racial bias is particularly stark in cases where numerous defendants were exonerated together. Separate from the individual exonerations listed in the National Registry, an additional 1,840 defendants have been cleared in fifteen “group” exonerations across the country since 1989. The great majority of these groups were framed for drug crimes that never happened and, likewise, a great majority of these groups were predominantly black.

Other racial biases are evident in Gross’s analysis. For instance, sexual assaults by black men against white women are a small minority of all sexual assaults in the U.S., but they make up half of sexual assaults with eyewitness misidentification.

Other disturbing trends reinforce the widely-documented racial bias that blacks face at every step of the system. They are more likely to be targets of police misconduct. They receive harsher sentences than whites for the same crimes. And, for violent crimes like murder and sexual assault, they spend several years longer in prison before exoneration.

Other studies from academic institutions and the federal government have also highlighted racial disparities in law enforcement and sentencing. The Justice Department, for example, released a study in 2015 that found black men received roughly 5% to 10% longer prison sentences than white men for similar crimes.

“Even those who are eventually freed have lost large parts of their lives—their youth, the childhood of their children, the last years of their parents’ lives, their careers, their marriages,” Gross says. “False convictions wreak havoc in every direction.”

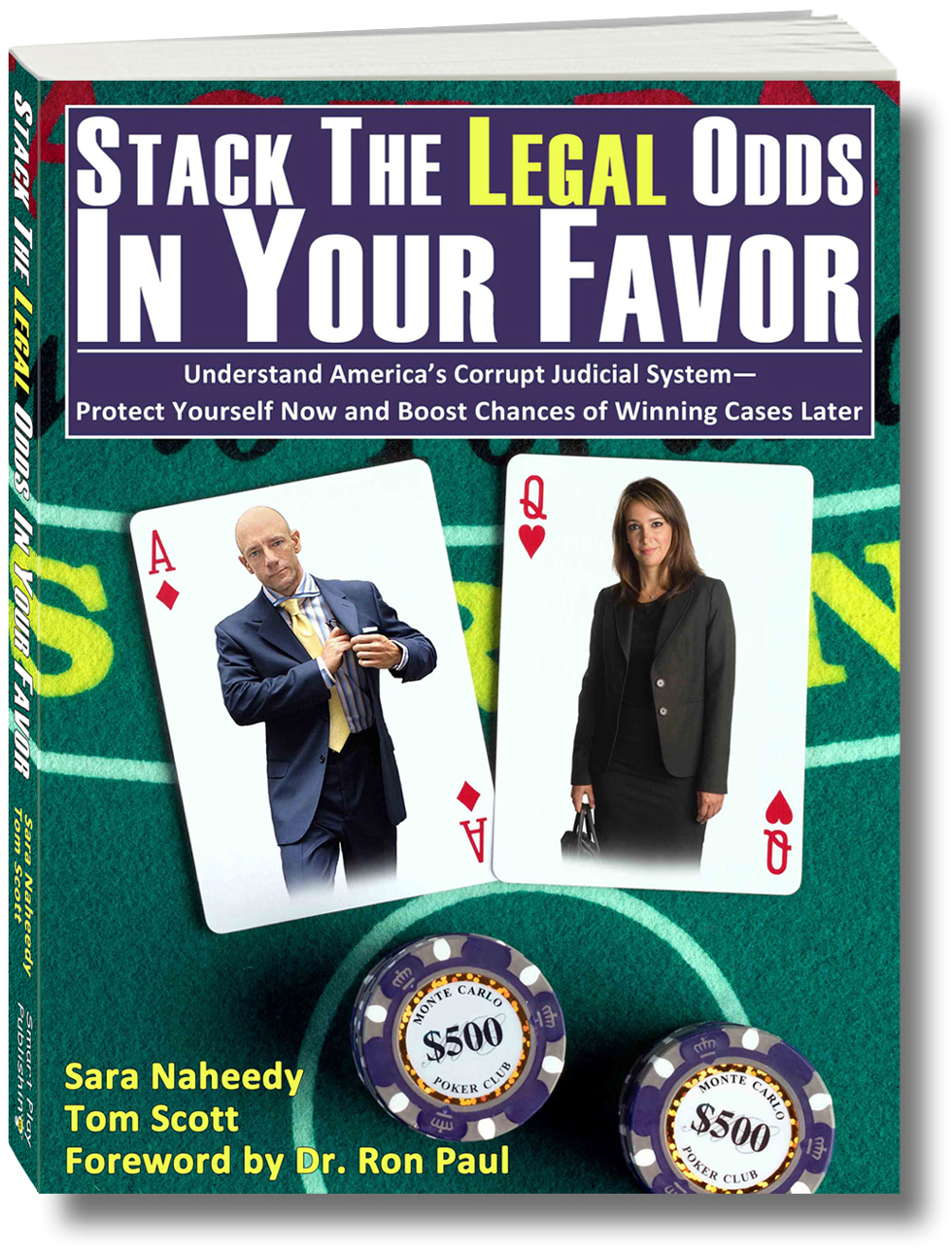

"The most important book written this century for Americans!"

"The most important book written this century for Americans!"

Comments

If you want to comment as a guest without signing in with social media and without signing up with Disqus:

1 – Enter your comment2 – Click in the Name box and enter the name you want associated with your comment

3 – Click in the Email box and enter your email address

4 – Select "I'd rather post as a guest"

5 – Validate the CAPTCHA and then click the arrow

comments powered by Disqus