Three Strikes (and You're Out) Laws—Why These Laws Are Bad

History

In the United States, habitual offender laws, commonly referred to as "three-strikes laws" were first implemented on March 7, 1994, and are part of the Department of Justice Anti-Violence Strategy. These laws require two previous convictions in order to be applicable and sometimes make life in prison mandatory. Twenty-eight states have some form of a three-strikes law. Its purpose is to drastically increase the punishment of those convicted of more than two felonies, but, in some instances, convictions of more than just one criminal offense, not necessarily a felony, will still result in harsher penalties as it does in Washington, D.C.

For more than twenty years, state and federal crime control policies have been based on the belief that harsh sentencing laws will deter people from committing crimes. But today, with more than two million people behind bars and state budgets depleted by the huge costs of prison construction, we are no safer than before. New approaches to the problem of crime are needed, but instead, our political leaders keep serving up the same old strategies.

Criticism

Some criticisms of three-strikes laws are that they significantly increase the prison sentences of persons convicted of a felony who have been previously convicted of two felonies, sometimes specific types, and limits the ability of some offenders to receive a punishment other than a life sentence. They also clog the court system with defendants taking cases to trial in an attempt to avoid life sentences and clog jails with defendants who must be detained while waiting for these trials because the likelihood of a life sentence makes them a flight risk. Part of the problem with these ridiculous laws results from the kinds of felonies that are considered part of the three-strikes formula. For example, robbery in California is one such felony. Stealing a small amount of cash to buy food could land someone in jail for a very long time.

In fact, some people have been given life sentences for offenses such as stealing one dollar in loose change from a parked car, possessing less than a gram of narcotics, and attempting to break into a soup kitchen. Furthermore, three-strikes laws are really just a new twist on an old theme. Many states have had habitual offender laws and recidivist statutes for years. All such laws already impose stiff penalties, up to and including life sentences, on repeat offenders. Overlap in laws is unnecessary, redundant, and expensive. Life imprisonment is also an expensive correctional option—and potentially inefficient given that many prisoners serving these sentences are elderly and therefore require more costly health care services and are statistically at low risk of recidivism. Dependents of prisoners serving long sentences may also become burdensome on welfare services.

Prosecutors have also sometimes evaded the three-strikes laws by processing arrests as parole violations rather than new offenses or by bringing misdemeanor charges when felony charges would have been legally justified. Likewise, there is potential for witnesses to refuse to testify and juries to refuse to convict if they want to keep a defendant from receiving a life sentence. This can introduce disparities in punishments, defeating the goal of treating third-time offenders uniformly.

Three-strikes laws have also been criticized for imposing disproportionate penalties and focusing too much on street crime rather than white-collar crime. Three strikes have a disproportionate impact on minority offenders. Racial bias in the criminal justice system is rampant. African American men, in particular, are overrepresented in all criminal justice statistics: arrests, victimizations, incarceration, and executions. This imbalance is largely the result of the "war on drugs." Although studies show that drug use among blacks and whites is comparable, many more blacks than whites are arrested on drug charges. Why?

The reason is that the police find it easier to concentrate their forces in inner city neighborhoods where drug dealing tends to take place on the streets than to mount more costly and demanding investigations in the suburbs where drug dealing generally occurs behind closed doors. Today, one in four young black American men is under some form of criminal sanction, be it incarceration, probation, or parole. Because many of these laws include drug offenses as prior strikes, more black than white offenders will be subject to long or life sentences under a three-strikes law.

The punishment should fit the crime, a constitutional principle. Under our system of criminal justice, the punishment must fit the crime. Individuals should not be executed for burglarizing a house nor incarcerated for life for committing relatively minor offenses, even when they commit several of them. This principle, known as "proportionality," is expressed in the Eighth Amendment to the Bill of Rights: "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

Many of the three-strikes laws depart sharply from the proportionality rule by failing to take into consideration the gravity of the offense. Pennsylvania's proposed law treats prostitution and burglary as strikes for purposes of imposing a life sentence without parole. Several California proposals provide that the first two felonies must be "violent," but the third offense can be any felony, even a non-violent crime like petty theft. Such laws offend our constitutional traditions. The three-strikes proposals are based on the mistaken belief that focusing on an offender after the crime has been committed, which harsh sentencing schemes do, will lead to a reduction in the crime rate.

But if 34 million serious crimes are committed each year in the U.S. and only 3 million result in arrest, something must be done to prevent those crimes from happening in the first place. Today, the U.S. has the dubious distinction of leading the industrialized world in per capita prison population, with more than two million men and women behind bars. The typical inmate in our prisons is minority, male, young, and uneducated. More than 40 percent of inmates are illiterate; one-third were unemployed when arrested. This profile should tell us something important about the link between crime and lack of opportunity—between crime and lack of hope.

Solution

Part of the solution will come when we begin to deal with the conditions that cause so many of our young people to turn to crime and violence. Only then will we begin to realize a less crime-ridden society. Another part of the solution will come when we finally understand that the system is the problem and not the solution. Moreover, every time laws are generated, the system is made worse, not better. There are already far too many laws in the nation—in fact, well over 1,000,000 and counting. We should be eliminating laws, not creating new ones. Three-strikes laws have the same affect upon corruption in our courts that dowsing a fire with gasoline has on the fire. As Tacitus said, "The more corrupt the state, the more numerous the laws."

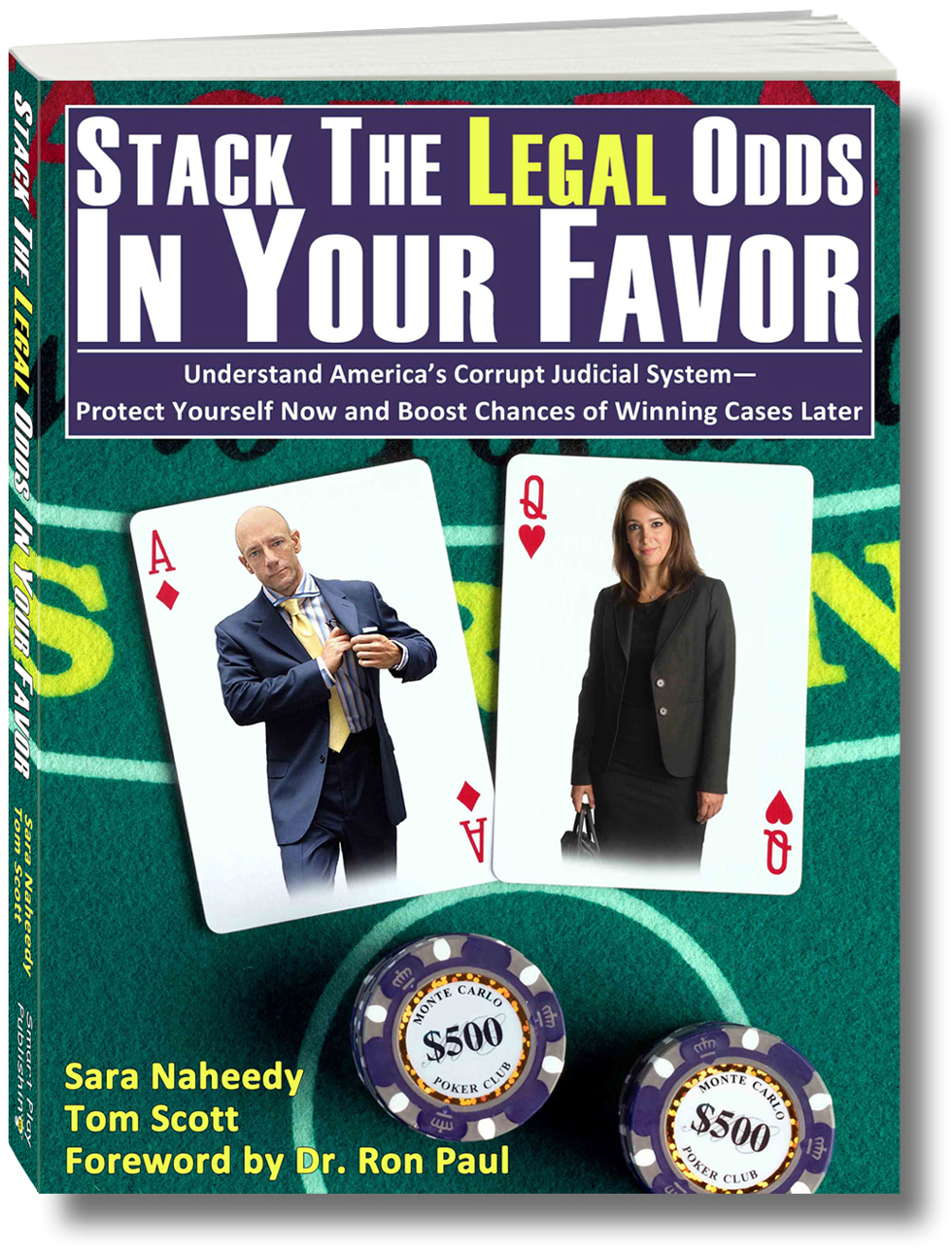

More about three-strikes laws, such as protecting yourself from becoming a victim of these and other selectively enforced or obscure laws, can be found in the informative and absolutely essential book Stack the Legal Odds in Your Favor. Save an additional 5% off your purchase by using this link.

"The most important book written this century for Americans!"

"The most important book written this century for Americans!"

Comments

If you want to comment as a guest without signing in with social media and without signing up with Disqus:

1 – Enter your comment2 – Click in the Name box and enter the name you want associated with your comment

3 – Click in the Email box and enter your email address

4 – Select "I'd rather post as a guest"

5 – Validate the CAPTCHA and then click the arrow

comments powered by Disqus